The Manga Moveable Feast for Ai Yazawa’s Paradise Kiss is underway. As I sometimes like to do, I’m going to take a second look at a Flipped column I wrote at some point in 2005, I think. So heaven only knows how much freshening it’s going to require. Updates will appear bracketed in italic.

*

There’s been a dust-up on the comics internet over the past week or so. It started at The Engine, Warren Ellis’s forum, with a discussion of Tokyopop’s contracts for the creators of its Original English Language manga. What started as a conversation about creators’ rights has spun off far and wide into sometimes heated exchanges over creativity, independence, and risk. It’s charged with generational conflict, creative philosophy, big dreams, and bitter experience. [Man, remember when Ellis was the hot club owner of the nerd internet and all the kids would hang out there? Probably not, but this was the first big controversial deal I remember coming out of The Engine, and it got nasty. This was back when people cared about manga-ka being appropriately compensated before the current post-legal era. Also, I’m older than Warren Ellis, which is depressing, but what can you do? Still, nobody should be older than Warren Ellis except maybe Alan Moore.]

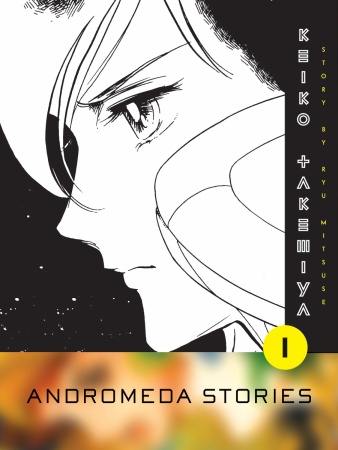

Throw in some sex and wry humor, and it would make a pretty terrific manga. Add some gorgeous art, and you’d have Ai Yazawa’s Paradise Kiss.

Throw in some sex and wry humor, and it would make a pretty terrific manga. Add some gorgeous art, and you’d have Ai Yazawa’s Paradise Kiss.

Nana, Yazawa’s current series, is getting lots of buzz lately. It’s a perennial best-seller in Japan, with a recently released live-action movie. It’s currently being serialized in Viz’s Shojo Beat, and I like what I’ve seen. But I’ve decided to go the tankoubon route, preferring to consume my manga in digest-sized chunks rather than monthly chapters. [This ended up being not entirely true, as I did intermittently pick up a copy of Shojo Beat every now and then, so I’m not really responsible for the demise of the magazine. I particularly renewed my devotion when Honey and Clover and Sand Chronicles launched. Why is it taking Viz so long to start a Shojo Beat web portal? Do they not think that teen-aged girls and middle-aged gay men like to sample comics online?]

So I’ll have to content myself with frequent readings of Paradise Kiss, which has a lot of things going for it. I can think of ten right off the top of my head:

1. The art. Paradise Kiss is glorious to look at, which is only apt with its high-fashion milieu. Yazawa’s character designs are terrific, richly detailed and endlessly expressive. Settings are vivid and rendered with care. While Yazawa employs some familiar shôjo techniques, her work doesn’t look like any other shôjo title on the shelves. There’s a much higher panel count than average, but pages still have the fluidity and elegance of composition that characterizes the best shôjo. At the same time, it has an edge to it that’s surprising. And while Yazawa clearly adores rendering all kinds of couture, her illustrations are never fashion-spread flat. She may revel in an eye-popping outfit, but she never forgets the person wearing it. [I think Yazawa may have improved slightly between Paradise Kiss and Nana, but she may just have hired a larger staff of assistants to take some of the load off.]

2. The plot. Stripped to its bones, the plot of Paradise Kiss sounds like magic-girl manga. An average schoolgirl is swept into a world of creation and illusion, surrounded by mysterious, exotic people, finding hidden strengths and romance along the way. In this case, though, it’s cranky, middling student Yukari discovering the transformative power of style and passion. The exotics are student designers at Yazawa School for the Arts, who want leggy Yukari to model for them in a competition. As Yukari spends more and more time with the designers of Paradise Kiss, she questions her priorities. Her world view expands, and she finds the courage to chart her own course in life. It’s really that simple, but Yazawa fleshes it out with poignant emotional detail. [There’s also the prince-bad boy dyad of love interests, which is very popular in some magic-girl stories. Will Yukari connect with the ostensibly ideal but possibly dull guy from her class, or will she make it work with the hot, conceited bisexual clothing designer? Oh, we all know the answer to that before Yazawa even tells us, don’t we?]

3. Yukari. Nicknamed Caroline by her new friends, Yukari isn’t always the most agreeable tour guide. She’s short-tempered, sarcastic, and given to hysterics. She makes bad choices and acts rashly. But she learns, taking responsibility for her actions and doing her best to stick to her decisions. Over the course of the manga’s five volumes, she goes from pretty kid to lovely person, and it’s a pleasure to watch it unfold.

4. Miwako. At first glance, the reader might be justified in cringing at the sight of wide-eyed, childlike Miwako and wince at her tendency to refer to herself in the third person. But before you can write her off as another cutesy kewpie doll, it becomes evident that there are all kinds of layers under the ribbons and curls. She’s got a heart of gold and a spine of steel, and her friendship with Yukari is genuinely touching. Her relationship with ill-tempered punk Arashi is equally surprising. Their connection is conflicted, but it’s very layered and mature. In spite of her doll-like appearance and demeanor, she carries a lot of the book’s emotional weight like a champ. [While I like Arashi and Miwako’s moments of conflicts and connection, I actually think I prefer the bits where George willfully triggers Arashi’s gay panic. I love seeing fictional gay guys’ egos get the better of them to the point that they actually believe someone of George’s impeccable standards would be attracted to them.]

4. Miwako. At first glance, the reader might be justified in cringing at the sight of wide-eyed, childlike Miwako and wince at her tendency to refer to herself in the third person. But before you can write her off as another cutesy kewpie doll, it becomes evident that there are all kinds of layers under the ribbons and curls. She’s got a heart of gold and a spine of steel, and her friendship with Yukari is genuinely touching. Her relationship with ill-tempered punk Arashi is equally surprising. Their connection is conflicted, but it’s very layered and mature. In spite of her doll-like appearance and demeanor, she carries a lot of the book’s emotional weight like a champ. [While I like Arashi and Miwako’s moments of conflicts and connection, I actually think I prefer the bits where George willfully triggers Arashi’s gay panic. I love seeing fictional gay guys’ egos get the better of them to the point that they actually believe someone of George’s impeccable standards would be attracted to them.]

5. Isabella. I was initially a bit annoyed by the suspicion that Isabella, the elegant transvestite, would stay too far in the background, looking lovely and composed and not doing much of anything. And while it’s true that she gets the least amount of time in the spotlight, well, somebody has to be the grown-up in this crowd. Isabella is the quiet, reassuring eye of a storm of self-reinvention, and it makes perfect sense. Isabella has already reinvented herself to her own satisfaction, so who better to nurture her works-in-progress friends?

6. Hiro. In many other shôjo stories, Hiro would be the… well… hero. He’s handsome, popular, studious, and kind. It’s a testament to the appealing weirdness of the Yazawa Arts crowd that Hiro is left spending most of his time on the margins, worrying over Yukari’s well-being and future. But there’s something compelling about his decency, and I found myself rooting for him every time he appeared. He isn’t the flashiest character, but he strikes a chord.

7. The faces. When characters cry in Paradise Kiss, their soulful eyes don’t glisten with aesthetically pleasing tears. They cry ugly, faces contorted with frustration and sorrow. When they laugh, you can hear it. A blush isn’t just a flattering flutter of shadow across the cheekbones. Yazawa’s characters feel big and show it, which brings readers even further into their emotional states.

7. The faces. When characters cry in Paradise Kiss, their soulful eyes don’t glisten with aesthetically pleasing tears. They cry ugly, faces contorted with frustration and sorrow. When they laugh, you can hear it. A blush isn’t just a flattering flutter of shadow across the cheekbones. Yazawa’s characters feel big and show it, which brings readers even further into their emotional states.

8. The complexity. Those emotional states aren’t cut and dried. Yukari embarks on an ill-advised romance with suave, bisexual George, the creative force behind Paradise Kiss and owner of a set of designer emotional baggage. While a lot of shôjo romances make mileage out of those standby traumas – Does he love me? Does he even know I’m alive? – Paradise Kiss asks harder questions. Yukari is swept away by George’s charm even as she’s repelled by his arrogance. She doesn’t wonder if George loves her so much as if he loves her enough, and she isn’t proud of what she’s doing to herself to be with him. It’s not a question of “will-they/won’t-they”; it’s more “should they?” [By “complexity,” I also mean “sadness,” because things don’t end the way you might expect them to in a manga of this category. There’s real disappointment and pain, though everything ends up being for the best, which is a really rare argument for a shôjo manga-ka to make.]

9. The words. I wonder sometimes if I don’t give enough credit to the translators and adaptors who work in the manga industry. Part of it comes from my complete inability to read Japanese, so I’m reluctant to single out that part of the process when I can’t make any kind of informed comparison. But the group responsible for the English-language of Paradise Kiss has given readers a sharp, layered script. The characters have distinct voices. The comedy has punch, and the drama is rich with memorable turns of phrase.

10. Holes in the fourth wall. I’m usually a big fan of the fourth wall, and I can find coy meta references a little irritating. But Yazawa has a real facility for these moments, when her characters wink at the audience. They make for some delightful levity, and given the hyper-dramatic nature of her cast, they make a weird kind of sense. Instead of undermining the world of the manga, they contribute to its charm and even its coherence. (And if Yazawa didn’t indulge in them, I’d have been deprived of the exchange where Isabella tells George that he’s failing to live up to the manga hero standard.)

So if, like me, you’re waiting for the trade on Nana, you should really consider wiling away the weeks with Paradise Kiss. It’s an engrossing, unconventional shôjo.

[I sort of neglected George in this, didn’t I? One would conclude that I don’t like him, or that he ranks eleventh or lower. I don’t really dislike George, but he always felt more like a catalyst in terms of this particular story. To my thinking, this is because he’s the character with the clearest view of what his future will be like. He’s written the interviews and can hear the glowing reviews in his head. There are variables in this future, and I don’t think he’s biding his time with Yukari. I genuinely believe that he’s open to a future with her, but I also believe he recognizes the possibility that she won’t be a part of the future he imagines for himself. He feels for her, but she’s not one of the givens of his future. I think that’s a fascinating stance for a character to assume, but it doesn’t make him immediately likable, if that makes any sense.

[I’m sure there’s fan fiction that features George’s future romantic misfortunes, and there’s probably stacks of doujinshi that features a full range of possible boyfriends for him. I’d be willing to read them, especially if they believably portray him getting his heart broken.]

Posted by davidpwelsh

Posted by davidpwelsh